Various Sources

A number of actors prevented Taylor from obeying this order immediately. Lt. Colonel Ethan Allan Hitchcock, the commander of Taylor's 3rd Infantry Regiment, described the Corpus Christi campsite as a focus of disease and pestilence. Brackish water, a poor diet, poor tents, camp sanitation, temperature fluctuations and an inadequate supply of firewood soon put a large number of the men on the sick rolls.

A number of actors prevented Taylor from obeying this order immediately. Lt. Colonel Ethan Allan Hitchcock, the commander of Taylor's 3rd Infantry Regiment, described the Corpus Christi campsite as a focus of disease and pestilence. Brackish water, a poor diet, poor tents, camp sanitation, temperature fluctuations and an inadequate supply of firewood soon put a large number of the men on the sick rolls.

Then the march south began. On March 8, the first dragoons left the Corpus Christi site with some pieces of artillery and the rest of the army followed on the 11th. While officially 4,000 strong, it was missing those who had taken fevers at Corpus Christi and those who had deserted through the swamps.

Then the march south began. On March 8, the first dragoons left the Corpus Christi site with some pieces of artillery and the rest of the army followed on the 11th. While officially 4,000 strong, it was missing those who had taken fevers at Corpus Christi and those who had deserted through the swamps.

Eventually,a group, the San Patricio Batallion ended up fighting for Mexico and many wre handed upon the taking of the Catle of Chapultepec on orders from Winfiled Scott.

Eventually,a group, the San Patricio Batallion ended up fighting for Mexico and many wre handed upon the taking of the Catle of Chapultepec on orders from Winfiled Scott.

"In June and July 1846, volunteer regiments that had been formed in response to the declaration of war began to arrive, swelling the size of the Army of Occupation to more than 10,000. The volunteer regiments’ failure to take adequate sanitation precautions soon turned the camp into a quagmire of filth and disease, made all the more unbearable by blistering heat.

"In June and July 1846, volunteer regiments that had been formed in response to the declaration of war began to arrive, swelling the size of the Army of Occupation to more than 10,000. The volunteer regiments’ failure to take adequate sanitation precautions soon turned the camp into a quagmire of filth and disease, made all the more unbearable by blistering heat.

Even before the first battles of the Mexican-American war were fought at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Guerra, the U.S. Army under Zachary Taylor had a major problem with deserters.

Suddenly, soldiers who had traveled with Taylor's Army of Observation and been transformed into an expeditionary force and, much later, an army of occupation.

This came after the President James Polk's had named John Slidell’s as his emissary and handed him the official task of negotiating a deal with Mexico. Polk Slidell to offer a settlement of all U.S. claims against Mexico, in exchange for recognition of the Rio Grande as the boundary between the two nations. In addition, Polk instructed Slidell to try and buy California for $25 million.

The Mexicans rejected Slidell and his mission outright and informed him he would not be received. He responded to President Polk by hinting that the Mexican reluctance to negotiate might require a show of military force by the United States. Based on this intelligence, Polk ordered Taylor to head for the Rio Grande. Slidell remained in Mexico until March 1846, but left as war became unavoidable.

The Mexicans rejected Slidell and his mission outright and informed him he would not be received. He responded to President Polk by hinting that the Mexican reluctance to negotiate might require a show of military force by the United States. Based on this intelligence, Polk ordered Taylor to head for the Rio Grande. Slidell remained in Mexico until March 1846, but left as war became unavoidable.

The troops under Taylor – about 4,000 strong, the bulk of the U.S. Army at the time – got a first taste of what awaited them as they made their way from Corpus Christi when they made their way down into South Texas.

Secretary of War William Learned Marcy had issued the order to Taylor to head out from Corpus Christi to the mouth of the Rio Grande on January 13, 1846 and reached the general on Feb. 3.

"The army was badly supplied, the insufficient trains trailing far behind it. It had little discipline, it's equipment was scanty and shoddy, and its arms were a chaos of diverse and mostly obsolescent models – smooth-bore muskets, flintlock and percussion-cap rifles, a handful of Hall's breech-loaders, a good many of the "Harpers Ferry" rifles mostly made by Eli Whitney Jr., and even a few repeaters. It had never moved as an army. Neither Taylor nor any of his juniors could maneuver it. Textbooks of drills and tactics were in everybody's saddlebags, for consultation en route, and Taylor had a healthy democratic contempt of the West Pointers who knew the things he badly needed to know.

"But anything was better than the stagnation of Corpus Christi and they were off for the Halls of Montezuma. There were swamps at first, then a waterless stretch, finally the chaparral country. food was bad and there was never enough water under the Southern sun. It was a land rich in rattlesnakes, which buzzed by the hundreds underfoot and slid into blankets by night. Mirages flared across the horizon and there were more rumors than rattlesnakes and mirages lumped together.

"On March 20 the advance reached the Arroyo Colorado, a salt pond, where General Francisco Mejia, who commanded Matamoros, drew up some skirmishers and and informed the Americans that if they came any farther they would begin a war. The advance splashed through; the first headlong flight of the Mexican army was well started before they reached the farther bank..."

Mejia, whose ornate language in his exhortations to the population under his care far surpassed Taylor's dry prose, had, just two days before, in Matamoros, issued one of those grandiose declarations so typical of Mexican officials.

"The cabinet of the United States...not only aspire(s) to the possession of the department of Texas, but it covets also the regions on the left bank of the Rio Bravo. Its army, hitherto for some time stationed at Corpus Christie, is now advancing to take possession of a large part of Tamaulipas; and its vanguard has arrived at the Arroyo Colorado, distant eighteen leagues from this place. What expectations, therefore, can the Mexican government have of treating with an enemy, who, whilst endeavouring to lull us into security, by opening diplomatic negotiations, proceeds to occupy a territory which never could have been the object of the pending discussion? The limits of Texas are certain and recognized; never have they extended beyond the river Nueces; notwithstanding which, the American army has crossed the line separating Tamaulipas from that department."

This did nothing to stop the advancing American troops to what they though was a better, more sanitary place from which to attack the Mexicans. But that turned out to be a false hope.

Conditions deteriorated still further when the army took up positions along the Rio Grande, and the desertions increased.

Hitchcock notes that American deserters had been shot while crossing the Rio Grande soon after the army arrived. "Probably they were just bored with army rations, but there was some thought that they might be responding to a proclamation of General (Pedro de) Ampudia's which spies had been able to circulate in the camp. Noting the number of Irish, French and Polish immigrants in the American force, Ampudia had summoned them to assert a common Catholicism, come across the river, cease 'to defend a robbery and usurpation which, be assured, the civilized nations of Europe look upon with the utmost indignation,' and settle down to a generous land bounty."

The earliest shooting of deserters as they swam the Rio Grande led the Whig press (Polk's enemy) into a sustained howl about tyranny. Bernard de Voto writes that in the House, John Quincy Adams sought to pass a resolution to court martial every officer or soldier who should order a killing of a soldier without a trial or inquiry into the reasons for the desertion. Although he was voted down, the theme of deserters was in every Whig speech on the conduct of the war.

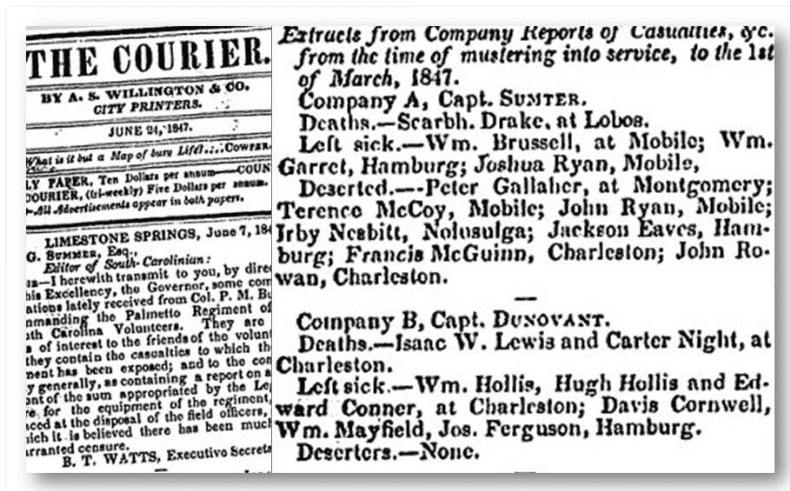

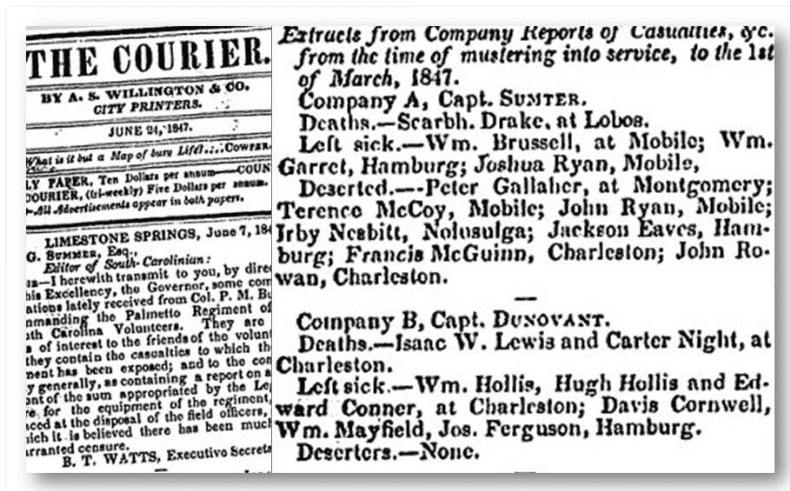

De Voto says that the National Police Gazette, a struggling periodical that had started out as a sports magazine, gained sound financial footing when it started printing the names of the deserters and the War Departmetn bought up big editions to distribute among the troops to discourage them from deserting.

Despite the executions, however, Tayor's army lost more than 200 soldiers before hostilties began.

Things only got worse after the fall of Matamoros when Taylor established his base of operations at Camargo, a village below the Rio Grande.

"In June and July 1846, volunteer regiments that had been formed in response to the declaration of war began to arrive, swelling the size of the Army of Occupation to more than 10,000. The volunteer regiments’ failure to take adequate sanitation precautions soon turned the camp into a quagmire of filth and disease, made all the more unbearable by blistering heat.

"In June and July 1846, volunteer regiments that had been formed in response to the declaration of war began to arrive, swelling the size of the Army of Occupation to more than 10,000. The volunteer regiments’ failure to take adequate sanitation precautions soon turned the camp into a quagmire of filth and disease, made all the more unbearable by blistering heat.

The troops suffered from a variety of diseases, such as influenza, smallpox, measles, malaria, and scurvy. However, dysentery caused the most problems. By the end of August, 1,500 troops, a staggering 12 per cent of Taylor’s force, had died of dysentery and other diseases.

The war with Mexico had the highest mortality rate of any of America’s wars, 110 per capita versus 65 per capita in the Civil War. In a typical regiment, more than 10 percent of the troops never lived to see the end of their enlistment. A significant percentage of these deaths were due to sickness and disease. Whereas 1,548 U.S. army deaths were combat-related, almost ten times that number, 10,970, fell to illness during the course of the war.

The volunteers succumbed to disease at twice the rate of regular troops. In addition to suffering from poor sanitation, the volunteers from rural areas were not immunized against smallpox, a requirement in the regular army. In the rush to raise troops, moreover, many states accepted volunteer recruits who were unfit for service."

4 comments:

The Anglos were animals, Juan. Animals!

The hillbillies came to die.

Thank You for the history lesson Juan. I mean that sincerely.

All written History is gossip, written by the winners.

Post a Comment