Even before the disaster, Scranton had been having a poor century.

In 1902 the Lackawanna Steel Company left north-east Pennsylvania in search of better access to transport and a less assertive labour force. The area still had coal, and enough spark to start new industries: in the 1920s a local button-maker became the country’s leading presser of 78rpm records. But after the second world war demand for coal fell.

Then, in 1959, miners working coal seams broke through the bed of the Susquehanna river, which flowed into the caverns below like bathwater swirling down a plughole. The mines never recovered.

The damage is in plain sight. The valley through which the Susquehanna runs is lined with shuttered factories. The city of Scranton faced near-bankruptcy in 2012.

The damage is in plain sight. The valley through which the Susquehanna runs is lined with shuttered factories. The city of Scranton faced near-bankruptcy in 2012.

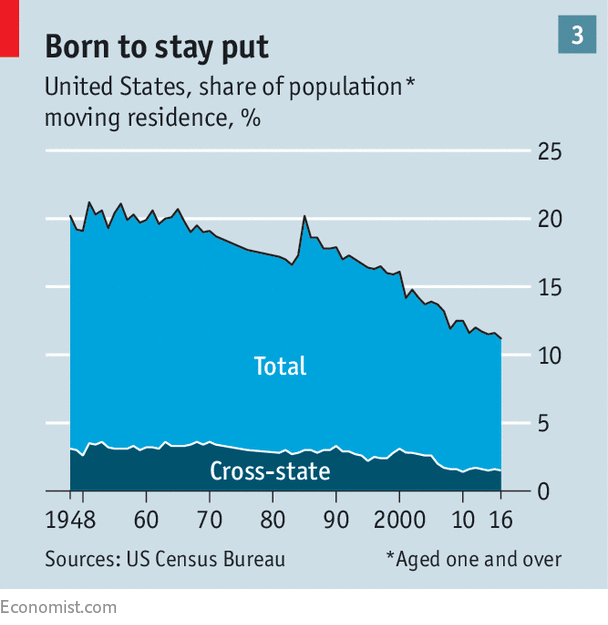

Yet despite almost a century of economic blows, more than half a million people remain in the area. It is a similar story in a host of other once-proud parts of the industrialised world. They have not found ways to thrive in a digitised, globalised economy. But they have not disappeared.

Yet despite almost a century of economic blows, more than half a million people remain in the area. It is a similar story in a host of other once-proud parts of the industrialised world. They have not found ways to thrive in a digitised, globalised economy. But they have not disappeared.Politicians have tried to help. State and local governments have spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the past decade on infrastructure and redevelopment projects in the Scranton area, just as they have in Britain’s Teesside, and France’s Pas-de-Calais.

By one estimate Pennsylvania spent over $6 billion between 2007 and 2016 on corporate subsidies, more than any other state. Much of that was dished out in its depressed north-east. But throwing money around is not enough. To improve the lot of left-behind places, policymakers need more determination and greater consensus on what works.

Do better they must. The forces that drive regional disparities are built into the mechanisms of globalisation, which makes them hard to resist.

Playing catch-up

Do better they must. The forces that drive regional disparities are built into the mechanisms of globalisation, which makes them hard to resist.

It is true that globalisation could stall or go into reverse. Indeed the desire that it should do so was part of the reason that voters in north-east Pennsylvania swung heavily to Donald Trump in 2016, delivering him the state.

It was in a similar spirit that areas of alienation in Britain, like Teesside, voted for Brexit and France’s economically battered north offered strong support to the Front National of Marine le Pen. But even if globalisation were to stop in its tracks, the regions it has weakened would not magically improve.

It was in a similar spirit that areas of alienation in Britain, like Teesside, voted for Brexit and France’s economically battered north offered strong support to the Front National of Marine le Pen. But even if globalisation were to stop in its tracks, the regions it has weakened would not magically improve.Economists once thought that, over time, inequalities between both regions and countries would naturally even out. Rich places with more money than investment opportunities would sink money into poorer ones with untapped potential; technological know-how would spread through economies. For much of the 20th century there was evidence to back this up.

Lagging industrialised countries grew much faster than the richest ones in the decades after the second world war.

In 1950, for example, real output per person in Italy was 33 percent of that in America; by 1973 it was 62 percent. From 1880 to 1980, income gaps across American states closed at an average annual rate of 1.8 percent: real personal income per person in Florida rose from 33 percent of that in Connecticut to 82 percent. Similar convergence occurred across Japanese prefectures and European regions.

At the same time, as geographical differences dwindled within and between industrialised economies, the gap between those economies and the rest of the world widened.

At the same time, as geographical differences dwindled within and between industrialised economies, the gap between those economies and the rest of the world widened.

American incomes, adjusted for living costs, were a bit less than nine times those in the world’s poorest countries in 1870, but nearly 50 times larger by 1990.

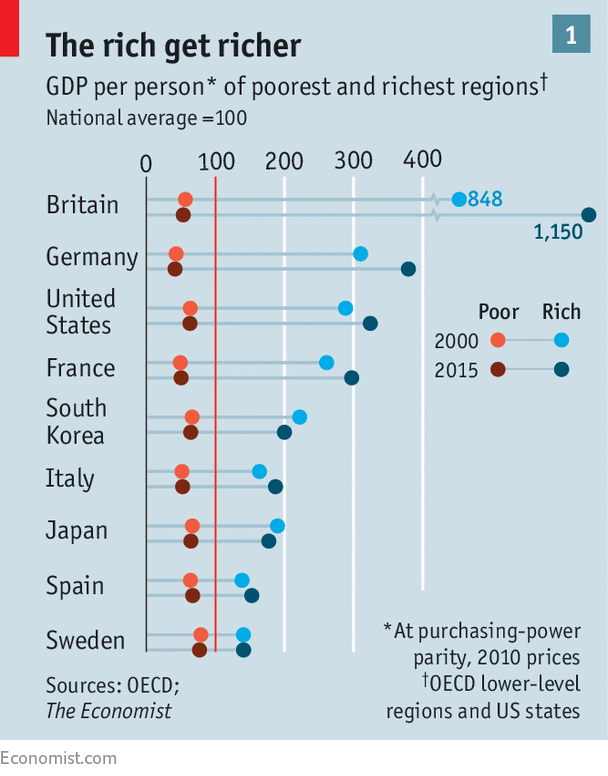

As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, both trends changed. Regional inequality within rich countries increased. Poorer economies began catching up with richer ones.

To read entire article, click on link: https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21730406-what-can-be-done-help-them-globalisation-has-marginalised-many-regions-rich-world

As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, both trends changed. Regional inequality within rich countries increased. Poorer economies began catching up with richer ones.

To read entire article, click on link: https://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21730406-what-can-be-done-help-them-globalisation-has-marginalised-many-regions-rich-world

No comments:

Post a Comment