By Juan Montoya

It was an idea that gathered steam in San Antonio, Houston, and across the country as automobile ownership rose in the late l800s and motorists demanded that roads – scarce everywhere, especially here – be paved to prevent them from getting stuck when it rained.

Why not use bricks made of wood to pave the streets?

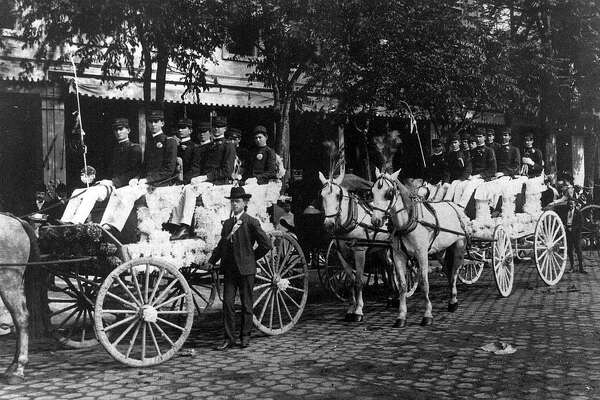

San Antonio used creosoted mesquite blocks to pave its downtown area as early as 1880 and the idea spread south. In February 6, 1911, the Brownsville city commission voted to create three paving districts in the downtown area and assess the property owners a fee per foot facing their properties.

This decidedly "South Texas" improvement to San Antonio's in the mid 1880s resulted in the laying of hexagonal mesquite blocks on Alamo Plaza. Mesquite was not only abundant, it was inexpensive. In fact it was essentially useless for much of anything else.

This decidedly "South Texas" improvement to San Antonio's in the mid 1880s resulted in the laying of hexagonal mesquite blocks on Alamo Plaza. Mesquite was not only abundant, it was inexpensive. In fact it was essentially useless for much of anything else.The gnarled wood is fairly durable and resistant to rot, a quality enhanced with the application of creosote. This, however, did not fully discourage swelling following heavy rain, which frequently led to an uneven road surface.

In the spring of 1911, the City Council determined the necessity of issuing bonds to support the city’s portion of the expense of paving efforts and ordered a bond election, which passed on March 14, 1911.

According to state law, the city was empowered to collect three-quarters of the cost of paving from abutting property owners, street car companies and railroad companies.

In August, the city contracted with the Creosoted Wood Block Paving Company of New Orleans to construct 23,650 yards (two miles) of paving and subsequently created paving districts in which to do the work.81 Paving District No. 1 included East Washington, East Elizabeth, and East Levee Streets, as well as East 10th through East 13th Streets. The paving was complete by December 1912.

According to the late Bruce Aiken, former Historic Brownsville Museum director, the treated wood was considered better than brick in the early twentieth century, but the fire department was called out to extinguish fires on the road caused by gas leaks common to early automobiles.

"The treated wood was better than brick but a lot of the early cars had gas leaks," Aiken said. "One time, a parked car was leaking gas and somehow, something caused it to catch fire.

"I think this is the only city in the United States where the fire department was called out because the street had caught fire," Aiken added.

The bricks would also buckle after heavy rains and eventually had to be completely removed. It wasn't until the late 1920s that we saw any paved roads in Brownsville. However, even into the the 1970s, when city crews dug below streets downtown, they would often encounter layers of the old bricks under the asphalt.

The bricks would also buckle after heavy rains and eventually had to be completely removed. It wasn't until the late 1920s that we saw any paved roads in Brownsville. However, even into the the 1970s, when city crews dug below streets downtown, they would often encounter layers of the old bricks under the asphalt. In the photos at right, one can see that the bricks were made out of different kinds of wood. They could be made out of mesquite, cedar and pine.

In the photos at right, one can see that the bricks were made out of different kinds of wood. They could be made out of mesquite, cedar and pine. The regular growth rings on the specimen at right indicate it was pine. Mesquite is more gnarled. The bottom shot shows that asphalt still on top of the wood block. This specimen came from the old Brownsville Public Works yard where they were stacked or anyone to take.

There is a Brownsville angle to the wood blocks used to pave streets in the early days.

There is a Brownsville angle to the wood blocks used to pave streets in the early days. Samuel W. Brooks, an architect, engineer, and builder, who was born in Pennsylvania in 1829 and later lived in Ohio, New Orleans, and eventually in 1863 moved to Matamoros, Tamaulipas where he remained until 1878 when he crossed the Rio Grande and came to Brownsville, played a role in this story.

Samuel W. Brooks, an architect, engineer, and builder, who was born in Pennsylvania in 1829 and later lived in Ohio, New Orleans, and eventually in 1863 moved to Matamoros, Tamaulipas where he remained until 1878 when he crossed the Rio Grande and came to Brownsville, played a role in this story.Brooks eventually married into a local Mexican family, but in 1871 – while still living in Matamoros – obtained a patent to improve machines for making paving-wood blocks, the same wood blocks that were used to pave Brownsville streets.

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, he was the foremost architect, engineer, and builder in the Brownsville area. He served eight terms as city engineer of Brownsville, was superintending architect for the United States Courthouse, Custom House, and Post Office (1892, demolished), and built levees along the Rio Grande at Fort Brown in Brownsville and at Hidalgo.

Brooks married twice. After the death of his first wife, he married a local widow, Inez Falgout. He died in Brownsville on February 15, 1903. His home, which he designed, was moved from its original location on the corner of 13th and Jefferson streets in 1878 to its present location at the corner of 13th and Jackson streets.

7 comments:

should have used bagels instead, and the city would have fallen for the scam

Its Monday, lets celebrate America, a travesty of a holiday

"See the world!"

"Meet exotic people in strange lands!"

"Enrich your life and your wallet trading in spice and silk!"

"Leave your old life behind!"

Columbus

Juanito you wanna join in the spectacle?

I'm fortunate enough to have one of those wood blocks I pulled out of a pot hole that was on the corner of e Washington and 11th st. back around 1998.

When I went back the next day, the pothole had already been covered up.

I still have this treasured wood block but I do plan to donate it to one of our museums one day.

October 15, 2019 at 3:01 AM

So they can storage at HEB or their chicken coop or even throw it away. Remember the scam only.

wood for highways what a scam and the gringos were running this place bola de pendejos...

is there a patent? wood bricks funny lol

Gringo scams all over the country what you expect snow!

Post a Comment