By Praxedis G. Cavazos

Excerpts

In 1767 Salvador De la Garza had been granted Porcíon #88 (5,756.89 acres) in what is today Starr County, Texas.

a ranch on the north bank of the Rio Grande near the mouth, named it Rancho Viejo, becoming the first white settlement in the area near Brownsville, Texas (the site is today marked by a state historical marker placed by the Texas Historical Society - 1936).

De la Garza later applied for a grant to the surrounding land about 1772. The grant "El Potrero del Espiritu Santo" was officially bestowed to De la Garza by King Charles III of Spain on September 26, 1781. It encompassed fifty-nine and one-half leagues (263,369.9 acres) in what is today Cameron County, Texas.

De la Garza died, the land was broken up into sections that went to his heirs. Time passed. In 1836, Texas settlers stemming from settlements set up by empressario Moses (and later Stephen) Austin, who acquired land from the Mexican government north of the Nueces River near present day Austin, Texas, declared independence from Mexico.

One of the heirs was Estefena Goseascochea de Cavazos y de Cortina, who was born on 1792 in Ciudad Camargo, Nuevo Santander, Mexico and died November 10, 1867 at her ranch, Rancho El Carmen, Texas at the age of 75. But before she died, she saw the unraveling of her family's land holdings.

How?

Dr. Walter Prescott Webb in his book, "The Texas Rangers", published in 1935 wrote: "Not only were the Mexicans bamboozled by the political factions, but they were victimized by the law.

"One law applied to them and another, far less rigorous, to the political leaders and the prominent Americans. The Mexicans suffered not only in their persons but in their properties. The landholding Mexican families found their titles in jeopardy and if they did not lose in the courts, they lost to the American lawyers."

Such was the case of Doña Estéfana, members of her family and their grant. In 1852, Charles Stillman, after taking over a valuable portion which included the 1,500 acres in the present city of Brownsville and Fort Brown, from the Espíritu Santo Grant, continued his assault on the Espíritu Santo Grant, leading to the Cortina raids, the worst border disturbances in Texas history.

Juan N. Cortina is one of the most disputed figures in border history. Because Doña Estéfana’s son would not submit to intolerance and had the courage to stand against tyranny and oppression, he was branded a bandit (especially by his enemies) and by others a Latin Robin Hood. A military figure, he once captured Brownsville (September 28, 1859) and held it for 36 hours when he became incensed at American treatment of Mexicans whose lives were being destroyed by the post Mexican War occupation.

Such was the case of Doña Estéfana, members of her family and their grant. In 1852, Charles Stillman, after taking over a valuable portion which included the 1,500 acres in the present city of Brownsville and Fort Brown, from the Espíritu Santo Grant, continued his assault on the Espíritu Santo Grant, leading to the Cortina raids, the worst border disturbances in Texas history.

Juan N. Cortina is one of the most disputed figures in border history. Because Doña Estéfana’s son would not submit to intolerance and had the courage to stand against tyranny and oppression, he was branded a bandit (especially by his enemies) and by others a Latin Robin Hood. A military figure, he once captured Brownsville (September 28, 1859) and held it for 36 hours when he became incensed at American treatment of Mexicans whose lives were being destroyed by the post Mexican War occupation.

It was in this climate that the Mexican people of the area were ripe for a hero, one who would stand fortheir rights. As Webb wrote: "one who would throw off American domination, redress grievance, and

punish their enemies and just such a champion arose in the person of Juan N. Cortina."

He served as governor of Tamaulipas and was promoted to brigadier general by Mexican President Benito Juarez, who relied on Cortina’s control of the Custom House at Puerto Bagdad to continue the resistance to Archduke Maximilian and the French Imperialists.

"Whether you like him or not, he (Cortina) was one of the most important persons in South Texas." said Jerry D. Thompson (an authority on the history of the Rio Grande fFrontier) on November 7, 2004 at the Brownsville Heritage Museum, during an afternoon of history and book signing.

Doña Estéfana and the families filed suit to defend their title against Stillman’s Land Company. On January 15, 1852, the notorious Judge J. C. Watrous ruled in favor of the heirs of the Espíritu Santo Grant, giving them title to the land on which Brownsville was being built. Somehow, in the legal maneuvering which followed, Stillman's attorney Samuel Belden steered the courts and state authorities so that he ended up cheating his partners and with the deed to the Cavazos land.

Doña Estéfana, her families and her son, "Cheno" Cortina, suspected that the lawyers had worked together against the heirs of the grant. Their suspicions seemed well founded. There are indications that it was a series of clever, legal maneuvers that gained Stillman the land and the Cavazos families had to

sacrifice to obtain even a measure of justice. Owners of the land grant had to sacrifice the land on which Brownsville stood, and a league of land (4,428 acres) from Doña Estéfana was paid to attorneys in order to get them to secure her title to the rest of the grant. Proof of ownership was something the owners

of the land grants had to do over and over.

After gaining confirmation of title to the other fifty-eight leagues that made up the grant, Doña Estéfana gave up her title to the Brownsville land for $1. Fighting Stillman and company might have cost Doña Estéfana and her family the entire Espíritu Santo Grant, so the compromise was probably a wise decision. Concerning the litigation, many Americans felt that the whole Espíritu Santo Grant should have been thrown out on grounds that the owners were Mexicans.

With her land in their secure possession, Doña Estéfana and family continued to adjust to their lives quietly but as cautiously as ever.

In his Memoirs Col. John S. (Rip) Ford relates his encounters with Doña Estéfana’s family. She was ever regarded by the Americans as a faithful friend. During the Civil War, Ford was in charge of the defense of the Rio Grande Valley until the arrival of Col. Robert E. Lee on January 29, 1863.

punish their enemies and just such a champion arose in the person of Juan N. Cortina."

He served as governor of Tamaulipas and was promoted to brigadier general by Mexican President Benito Juarez, who relied on Cortina’s control of the Custom House at Puerto Bagdad to continue the resistance to Archduke Maximilian and the French Imperialists.

"Whether you like him or not, he (Cortina) was one of the most important persons in South Texas." said Jerry D. Thompson (an authority on the history of the Rio Grande fFrontier) on November 7, 2004 at the Brownsville Heritage Museum, during an afternoon of history and book signing.

Doña Estéfana and the families filed suit to defend their title against Stillman’s Land Company. On January 15, 1852, the notorious Judge J. C. Watrous ruled in favor of the heirs of the Espíritu Santo Grant, giving them title to the land on which Brownsville was being built. Somehow, in the legal maneuvering which followed, Stillman's attorney Samuel Belden steered the courts and state authorities so that he ended up cheating his partners and with the deed to the Cavazos land.

Doña Estéfana, her families and her son, "Cheno" Cortina, suspected that the lawyers had worked together against the heirs of the grant. Their suspicions seemed well founded. There are indications that it was a series of clever, legal maneuvers that gained Stillman the land and the Cavazos families had to

sacrifice to obtain even a measure of justice. Owners of the land grant had to sacrifice the land on which Brownsville stood, and a league of land (4,428 acres) from Doña Estéfana was paid to attorneys in order to get them to secure her title to the rest of the grant. Proof of ownership was something the owners

of the land grants had to do over and over.

After gaining confirmation of title to the other fifty-eight leagues that made up the grant, Doña Estéfana gave up her title to the Brownsville land for $1. Fighting Stillman and company might have cost Doña Estéfana and her family the entire Espíritu Santo Grant, so the compromise was probably a wise decision. Concerning the litigation, many Americans felt that the whole Espíritu Santo Grant should have been thrown out on grounds that the owners were Mexicans.

With her land in their secure possession, Doña Estéfana and family continued to adjust to their lives quietly but as cautiously as ever.

In his Memoirs Col. John S. (Rip) Ford relates his encounters with Doña Estéfana’s family. She was ever regarded by the Americans as a faithful friend. During the Civil War, Ford was in charge of the defense of the Rio Grande Valley until the arrival of Col. Robert E. Lee on January 29, 1863.

During the Cortina raids, Doña Estéfana moved temporarily from her ranch to Matamoros where she had other properties. In 1859 and soon after her return to Texas, on February 2, 1860, Col. Ford after a short patrol near Brownsville, with a small body of rangers and Don Sabas Cavazos, half-brother of Juan N. Cortina, arrived at Doña Estéfana’s ranch, El Carmen. Don Sabas invited the officers in the house, and they were introduced to Doña Estéfana.

Ford assured her that he and other Americans would do all they could to protect her and her property. Ford remembers what Doña Estéfana was like the day they met: "She was a small woman, not weighing more than one hundred pounds, being at the time over seventy years of age. She was very good looking, had a pretty face, bright black eyes and very white skin. She was a lady of culture and indicated as much in her actions and had all the politeness of a well-bred Mexican."

On April 1864, Col. Ford moved his family to Matamoros, Mexico in order that his wife might be near her mother who lived in Brownsville. Soon after her arrival in Matamoros, Sabas Cavazos and his half-brother Gen. Juan N. Cortina, then governor of Tamaulipas, called on Mrs. Ford and offered any assistance or financial aid which she might need. They were probably returning one of the courtesies which Ford had shown their mother.

The cemetery, established by Doña Estéfana prior to 1867 for her use, is said to be the oldest of the ranch cemeteries on the river road. The site probably sustained some damage during the hurricanes of October 6, 1867 and September 4-5, 1933, which devastated he Valley.

Ford assured her that he and other Americans would do all they could to protect her and her property. Ford remembers what Doña Estéfana was like the day they met: "She was a small woman, not weighing more than one hundred pounds, being at the time over seventy years of age. She was very good looking, had a pretty face, bright black eyes and very white skin. She was a lady of culture and indicated as much in her actions and had all the politeness of a well-bred Mexican."

On April 1864, Col. Ford moved his family to Matamoros, Mexico in order that his wife might be near her mother who lived in Brownsville. Soon after her arrival in Matamoros, Sabas Cavazos and his half-brother Gen. Juan N. Cortina, then governor of Tamaulipas, called on Mrs. Ford and offered any assistance or financial aid which she might need. They were probably returning one of the courtesies which Ford had shown their mother.

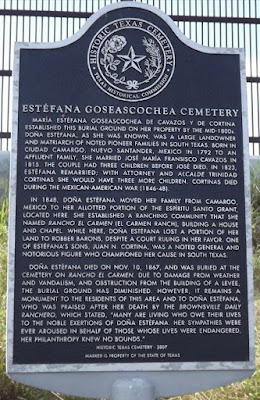

The Cemetery

The cemetery, established by Doña Estéfana prior to 1867 for her use, is said to be the oldest of the ranch cemeteries on the river road. The site probably sustained some damage during the hurricanes of October 6, 1867 and September 4-5, 1933, which devastated he Valley.

The devastation caused severe flooding of the area and prompted the U. S. International Boundary Water Commission to build a levee along the Rio Grande. The construction of the levee, however, left the

cemetery site on the south side of the levee and completely obscured it from view and made it practically inaccessible. It remained unnoticed for decades.

Locals hardly recall burials at this site after the construction of the levee and the hurricane and, if there were any burials, they were few and unnoticed. Her cemetery is located on what was once her property, Rancho El Carmen (El Carmen Ranch) in Cameron County, Texas, within what is known as the Espíritu

Santo Grant. Part of that grant was her allotted portion of the grant. The site is in Cameron County Precinct 2 in Rancho El Carmen, a community established and settled by Doña Estéfana in early 1840’s about four miles west of Brownsville on the Old Historic Military Telegraph Road (US Hwy. 281).

The Brownsville Daily Ranchero of November 13, 1867, praised her,: "Many are living who owe their lives to the noble exertions of Doña Estéfana. Her sympathies were ever aroused in behalf of those whose lives were endangered, her philanthropy knew no bounds."

When Doña Estéfana fell ill in the summer of 1867, one of her concerns was the well being of two orphans, Abel and Leandro, whom she had raised since childhood. In her will she named her son, Sabas Cavazos, tutor and guardian for the boys.

To fulfill her request she was buried in "El Campo Santo que yo tengo en este rancho de mi propiedad"

(cemetery that I have on this ranch of my property), near where her home once stood. Her funeral was largely attended.

Two months later after having obtained permission to return home, the Brownsville Ranchero of January 11, 1868, reported Juan N. Cortina’s last visit to the U.S.-Mexico borderland to pay his last respects to his deceased mother, Doña Estéfana.

cemetery site on the south side of the levee and completely obscured it from view and made it practically inaccessible. It remained unnoticed for decades.

Locals hardly recall burials at this site after the construction of the levee and the hurricane and, if there were any burials, they were few and unnoticed. Her cemetery is located on what was once her property, Rancho El Carmen (El Carmen Ranch) in Cameron County, Texas, within what is known as the Espíritu

Santo Grant. Part of that grant was her allotted portion of the grant. The site is in Cameron County Precinct 2 in Rancho El Carmen, a community established and settled by Doña Estéfana in early 1840’s about four miles west of Brownsville on the Old Historic Military Telegraph Road (US Hwy. 281).

The Brownsville Daily Ranchero of November 13, 1867, praised her,: "Many are living who owe their lives to the noble exertions of Doña Estéfana. Her sympathies were ever aroused in behalf of those whose lives were endangered, her philanthropy knew no bounds."

When Doña Estéfana fell ill in the summer of 1867, one of her concerns was the well being of two orphans, Abel and Leandro, whom she had raised since childhood. In her will she named her son, Sabas Cavazos, tutor and guardian for the boys.

To fulfill her request she was buried in "El Campo Santo que yo tengo en este rancho de mi propiedad"

(cemetery that I have on this ranch of my property), near where her home once stood. Her funeral was largely attended.

Two months later after having obtained permission to return home, the Brownsville Ranchero of January 11, 1868, reported Juan N. Cortina’s last visit to the U.S.-Mexico borderland to pay his last respects to his deceased mother, Doña Estéfana.

4 comments:

Beautiful synopsis of the history written in so many books about Dona Estefana that many of us have failed to read. It is a sad story, a big part of the history of Brownsville and left open to interpretation by each reader, but it does make us wonder and wish to have been a witness to the unfairness that has been documented in so many books - whether you like it or not. Good Job!

These land grant heirs were screwed out of their own land. For years Texas history has made Juan Cortina, as a villain, thief, and law breaker and many many more accusations, which in fact proves Texas itself was a liar, thief and law breaker. Texas was and still is run by corrupt political leaders. The judicial declared heirs that are still alive should have the right to rewrite the real Texans History. They should have the right to recognize and rejoice our True Spanish Heirs and Heroes. They were the true work horses the these settlements.

You can wipe you ass with your fucking Spanish Land Grants. Did the indigenous Peoples that lived here sign off on these Grants?

Well fuck no they didn't.

You don't get to start history wherever you want because it suits your narrative.

Spain's manifest destiny has no moral right to the New World than anyone else.

That's just it you idiot, these land grants were STOLEN. No Grantee nor heir signed off on them. Stolen. People or herds like you wouldn't understand because the INDIGENOUS humans are people like you. That came in wagon trains from heaven knows where to steal land, cattle, and even gathered salves to do your dirty labor jobs and then even sold them for money. They then have the nerve to write about Texas history to suit their disgust. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was to protect private land that was NOT Mexico nor Texas, but PRIVATE LAND GRANTS. You then have the nerve to rebuild your rat infected houses and sit them in Brownsville to mock the family of Salvador de la Graza and Juan Cortina. You are a disgust. You can't even answer your own question-did they sign off on the land grants.

Post a Comment