By Juan Montoya

The central library in Milwaukee, Wisc., is replete with foreign-language newspapers that popped up during the great migrations of Czechs, Poles, and German immigrants to the Midwest in the mid-1800s.In fact, all across the Midwest librarians have been attentive to preserving this part of their region’s history by collecting those publications which tell of the lives and travails of the immigrants to those areas.

“These little newspapers are invaluable to researchers and historians who want to know the day-to-day lives of these groups,” said Roxane Polzine, of the Minnesota Historical Society. “While English-language newspapers were generally interested with the dominant population, we have very little to document what was of concern to these communities. Their preservation is invaluable to any community’s history.”

Unfortunately, until recently no such effort had been made in the case of Spanish-language newspapers and weeklies that popped up in South Texas during the great migrations of Mexicans that occurred as a result of social upheavals an revolution across the Rio Grande in Mexico.

“We were getting everything in bits and pieces,” said Cirpiano A. Cardenas, a former University of Texas-Texas Southmost College assistant professor in Modern Languages. “Until recently, we didn’t know a lot about the history of Hispanics in the Rio Grande Valley, and Brownsville in particular.”

That changed in 1975, when the University of Texas, realizing the valuable asset these publications were to historians and scholars alike, purchased and catalogued 21 years of editions of the weekly El Puerto, founded and edited by Gilberto A. Cerda in Brownsville in January 1954.As Cardenas wrote in his study titled “Hispanic Journalism in Brownsville, Texas,”

“This weekly paper, founded in 1954...is the only complete record of Hispanic journalism available to scholars and the general public that chronicles the Mexican-American experience in Brownsville.”

Cardenas summarized the history of Hispanic newspapers in this border city back to the exodus from Mexico prior to the U.S. Civil War. During the occupation of Mexico by the French, pro-Benito Juarez exiles published El Zaragoza while Emile P. Claudon published the Rio Grande Courier, written in English, Spanish and French.

Upon Juarez’s triumph, these newspapers folded as their respective target populations returned to Mexico or went further into the interior. Four newspapers in Spanish were being published at the turn of the 20th Century, and one, El Cronista, which was founded in 1890, was the last Latino-owned, Spanish newspaper published in Brownsville. It ceased publication in the late 1920s, when many Mexicans returned to a more stable Mexico.

The 1950s brought a resurgence in Spanish-language newspapers as braceros (derisively called wetbacks then), or temporary workers, flooded South Texas. Cardenas documents at least six other Spanish-language newspapers were being published in the Rio Grande Valley in 1954 when El Puerto began publication. By the time it ceased publication in 1975, El Puerto was the lone Spanish-language newspaper being published in the Rio Grande Valley.

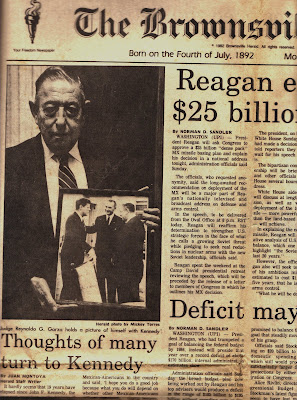

(In the photo above at right, a March 14, 1954 edition of El Puerto with its slogan that "Decir la Verdad es Servir a la Sociedad y el Pueblo que la Representa.")

According to his own account that Cerda wrote in the 15th Anniversary edition in 1969, six prominent Mexican-American community leaders approached him to start a weekly newspaper.

Cerda had been an apprentice at the English-language Brownsville Herald at 12, and worked at the daily for the next 32 years.

“(They wanted) to publish a weekly paper to defend the rights of the Latinos in this area, that at that the time were not as respected in this region.”

The start of the newspaper was inauspicious. Cerda described it in his own words.

“The print shop where the newspaper was born was rickety and the press was quite small, measuring 12 by 18 (feet) and without resources,” Cerda wrote. “Things being like that, your servant and (colleague) Leon Ledezma agreed to work together and we published the first edition...January 30, 1954.”

For the next 21 years, Cerda and different community supporters wove the news of the community in the eight-page tabloid that was published often under penurious circumstances using the goodwill of local businessmen and churches. In one instance, only four weeks into the operation, Ledezma had to leave town and Cerda was left to his own devices to put out the paper without a typesetter.

“We printed the paper the old-fashion way, stopping after each line, from first to last, from 10 to 12 points,” he wrote. “ I didn’t know whether or not El Puerto would continue to be published, because it’s very difficult to go on when there are no funds or resources.”

Fortunately, Cerda ran into the Rev. Miguel Guillen, the president of the local Latin American Council of Christian Churches that had its own print shop. For the next 12 years, that organization helped El Puerto survive. When Hurricane Beulah swamped El Puerto’s warehouse, the council again stepped in and donated money to help Cerda replace the newsprint that had been damaged by the storm.

Likewise, when El Puerto was sued “for telling the truth,” local jurist Reynaldo Garza, who later was nominated and confirmed as the first Mexican-American federal judge, defended it editors in two cases without charging them professional fees other than court costs.

And so, through the support of local residents, El Puerto continued telling the story of the people in South Texas. Its features, including one by Jesse Sloss, who was city commissioner and later city manager, named “Confetti y Ladrillazos” (Cardenas translates this as Thorns and Roses), drew its Hispanic readership through its criticism and praise on various issues of the day.

During a roundup of braceros in July 1954, Sloss expressed dismay at the actions of the Border Patrol as they scoured the city for those braceros who had stayed on after their work permits had expired.

“Poor people,” Sloss wrote. “It arouses a great deal of pity to see so much suffering in the world, but it is even more painful to see it in our own community! Men, women and children, entire families are in custody of government agents.

“One can see in their faces a profound sadness and a deep sense of desperation. They are worthy of our compassion because the crime they have committed is to try to make an honest living doing the work that ours don’t want to perform. What do these poor and unfortunate people take from us? Much to the contrary, instead of taking from us, they give, because they gather the harvest that would be lost, if it weren’t for them. Godspeed, little wetbacks, may God fill you with His blessing.”

Who was Gilberto Cerda?

Cerda was born in Brownsville in 1901 and until he died in 1975, lived through the tumultuous events that shook Mexico – and indirectly – South Texas and the U.S. Southwest. He was nine years old when Mexican Revolution began, and, personally witnessed the arrival of Mexicans fleeing that strife-torn land. When he was 15, Gen. Joseph John Pershing entered Mexico pursuing Pancho Villa in a vain attempt to capture him.

In the 1930s, as in the 1950s, he witnessed the Great Repatriation Campaign to return Mexican nationals (and some American-born Hispanics) back to that country as a result of the Great Depression, and later, the end of the Bracero Program. He was 40 when World War II broke out, and too old to go to war.

And he witnessed Mexican-American service men and women return from the Korean War (1950-1953), only to suffer discrimination back in their native country upon their return.

During the 1960s and 1970s, he witnessed the emergence of the Chicano Movement and the outbreak of the Vietnam War. Reflecting the conservatism of adult Mexican-Americans to the Chicano Movement, his columns often expressed disagreement with their ideology and methods of resistance. In sum, his writings reflected the conflict of the times, commenting on the changing political, social and cultural changes.

“He was very strict,” remembered his daughter Esther Cerda Castañeda, a teacher at De Castillo Elementary with the Brownsville Independent School District. “He used to say that if you brought a boyfriend home, it was that you were going to marry him.”

Another of his daughters, who also a teacher at Paredes Elementary, Mary E. Garza, agreed. She said their father kept strict rules at home and expected his children to follow them.

“He didn’t fool around,” said Garza. “If he said 11 p.m., he meant 11 p.m.”

Yet another of his daughters, Dolores Schrock, then a teacher at Perkins Intermediate School, recalls her father disapproving of women wearing slacks when their use became widespread in the 60s and 70s.

“He was very conservative when it came to morals and traditions,” she said.

“He was very conservative when it came to morals and traditions,” she said.

According to researcher Cardenas, Cerda’s columns were colored with moralisms and Mexican idioms (refranes) reflecting a deep adherence to the morals and conservatism of traditional South Texas and Northern Mexican Hispanic culture.

“Readers looked forward to the editor’s moralistic commentaries regarding various subjects, such as, juvenile delinquency, corruption, and the general decline of manners and morals in the community,” he wrote. “Cerda always used satire to criticize corruption and to ridicule what he perceived as excesses, particularly in the younger generation.”

Papa y Mama:” “Se pelearon como viejas tamaleras,” “Le jugaron el dedo en la boca,” “Hubo Zafarrancho en el Baile del Sol,” “La misma gata, nomás que ahora esta revolcada.”

In one front-page story dated Feb. 8. 1954, he reports on the apparition of the devil to a couple who had driven to a cemetery after a street dance to neck. In admonition to the parents, he warns them of the consequences of these “libertines” and cautions them against giving youth too many freedoms.

He railed against the popularity of the polkas in northern music and predicted their demise. And he yearned fondly for the days before the polkas when one could listen to real music like waltzes, “chotizes,” “contradanzas,” and “lanceros.”

The end for El Puerto came with the death of Cerda in 1975.

But until that time, the newspaper provided the only native account of Mexican-American existence in this border city.

For that, if for nothing else, it filled a critical niche and provided a valuable insight into the social and cultural history of border life. Border historians and scholars who can gain access to the archives at the University of Texas-Austin will be rewarded with a well-written chronicle of a quarter century of border history written from the popular viewpoint at the grassroots level.

As Cardenas states in his essay: “It is the only complete record of Hispanic journalism available to scholars and the general public that chronicles Mexican-American life in Brownsville.”

7 comments:

Juanito:

And now you continue the labor of giving a glimpse of the social and cultural and political situation of Brownsville: in English, in Spanish, in Tex-Mex, in Chicano and Spanglish etc

Ese urgullo de los pinches cocos wanna be white but can't, has done a lot of harm, but who cares as long as the Hispanic heritage is kept at home and the barrios pinches cocos can go to satanas and keep in mind mexicons from Mexico ain't gonna help.

Dang Juan, you’re picking on some scabs. I remember my great grandmother and her mother was full blooded Indian from the mountains in Mexico. No body knows anything about her. My grandpa was WWll veteran. Very true, a lot of history is lost with our culture. Unfortunately those of us in our 40’s and above probably went through racial shit. I know a lot of older veterans that still hold on to that. Proud men. You brought up the Korean War.

The Battle of Peleliu, codenamed Operation Stalemate II by the US military, was fought between the United States and Japan during the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign of World War II, from 15 September to 27 November 1944, on the island of Peleliu.

Read into that one, nasty battle. Thank you veterans.

Old HoBo, 🖕suck it..

These days have come and gone. People need to be proficient and efficient in English. Spanish is my primary language and I love the language. However, my experience has been that many people today do not know either Spanish or English.

I have seen Spanish speaking people spell "que" as "ke" and "went" as "whent." People just need to learn to communicate effectively...I am not a coco.

September 18, 2023 at 3:50 PM

NO SABO, blame la resaca telemetry for that.

At some point we realize that we need to take charge of our education. There was no way that I was not going to learn Spanish. Spanish was the language of my parents. Both my parents were able to read and write Spanish. English was the language at school. At a very early age I figured out that if I wanted to do my homework I needed to listen and pay attention to my school teachers because there was no one to help me at home. At home my strict hardworking parents were in charge of Spanish and religion.

The point is that it is up to the person to become a life long learner. If one chooses not to better themselves pues nimodo. It all has to do with the man in the mirror.

September 19, 2023 at 12:47 PM

sounds like a stell student, walking around with a mirror on your ^&*(

Post a Comment